Sep

14

Antwerp – Belgium’s National Redoubt

Filed Under History & Geography on September 14, 2014 at 10:16 pm

Note: myself and Allison Sheridan had a good discussion around this post on episode 488 of the NosillaCast podcast (starting at 51:34).

Note: myself and Allison Sheridan had a good discussion around this post on episode 488 of the NosillaCast podcast (starting at 51:34).

Between 1851 and the end of the first world war, the city of Antwerp was Belgium’s so-called National Redoubt. It was decided that it would not be feasible to defend all of Belgium, so, the defence should instead be focused on holding a defensible part of the country until help could arrive from one of the powers guaranteeing Belgian neutrality. The city chosen for this purpose was Antwerp.

The fortifications built around Antwerp were impressive, in scale and design, both from a military and architectural point of view. They are without a shadow of a doubt archeological treasures, especially the late 19th century structures designed by the acclaimed fortification designer General Brialmont. While the later works were all more advanced militarily, they were never as architecturally beautiful as the late-19th century Brialmont forts.

Ultimately, the National Redoubt would never prove a resounding military success, but that doesn’t take away from it’s cultural, architectural, or historic importance. The redoubt had a big impact on the nation as a whole, and much more so on the province of Antwerp. The engineering work was on a scale comparable to that of building a railway network, and while much of that work is, by design, not easily visible at ground level, it’s immediately obvious from the air if you know where to look.

The KMZ File

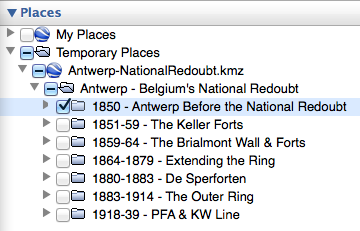

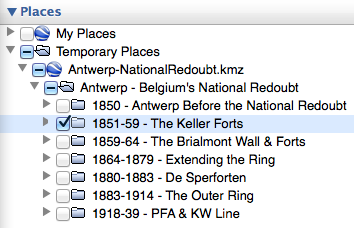

While the maps I have included with the article are useful, I strongly recommend downloading the KMZ file linked below and opening it Google Earth while you read this article for the fullest experience. The content is the same as that in the interactive maps, but the interface is much more immersive in Google Earth.

Download Antwerp-NationalRedoubt.kmz

The KMZ file is broken into sub-folders, one for each era of the national redoubt described in this article. Because many structures exist in multiple eras, there are multiple copies of them in the file. For what you are seeing to make sense, you should only enable one section at a time:

Antwerp Before 1850

Before telling the story of Antwerp as the National Redoubt, it’s worth taking a quick look at the wider history of the city of Antwerp, who’s history as a fortified city goes back centuries before the birth of Belgium as a nation (i.e. before 1830).

One of the first things you might notice when looking at an arial view of Antwerp (as seen above) is how asymmetrical it is. Many cities grow up along the banks of rivers, but most grow around those rivers more or less symmetrically. For example, look at how London surrounds the Thames, or Paris the Seine. Antwerp is different – for all but the last of its 17 centuries of existence, it has occupied just the east bank of the river Scheldt. Locals refer to this heavily populated east bank as the right bank. In contrast, the left bank has been mostly just farm land for centuries. The little bit of development you see there today is almost all less than a century old.

This strange layout makes little to no sense until you look at old maps of the area. Today, the river has one very well defined channel, and the land on both banks is well drained solid land. Historically, things looked very different. Antwerp was built at the start of the river’s massive estuary, so there were many channels and islands, and much of the land between those channels was low-lying salt marsh or tidal wetland. Over the centuries these wetlands have been encircled with dykes and drained to form so-called polders. As these polders grew and joined up, many former islands were incorporated into the mainland, and all but one river channel was closed. That one remaining channel became ever more confined and ever more well defined, putting an end to the river’s natural wandering over time.

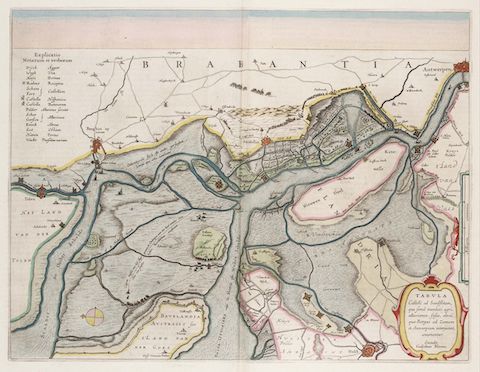

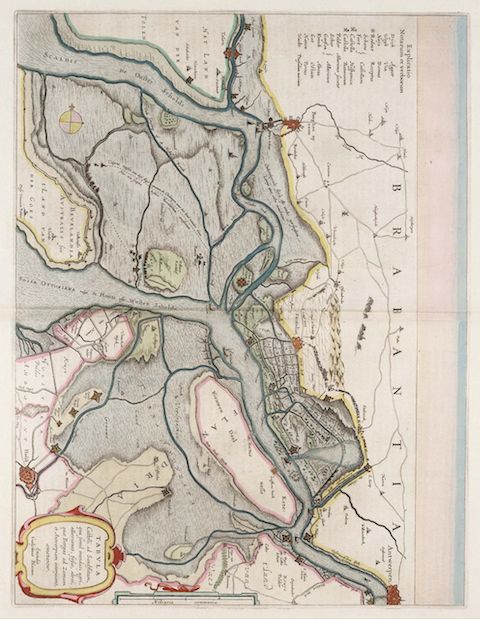

The map below dates to 1664, it shows multiple river channels and now-vanished islands, but even that map already shows many polders.

This map doesn’t have north at the top, so it might be helpful to see it rotated by about 90 degrees clockwise:

If you look closely at the current Google Earth imagery you can still see the line where the re-claimed polder land meets a former island near Doel (marked in blue in the image below):

As well as all the now vanished river channels and marshes, you’ll also notice there are a lot of fortifications marked on the 1664 map. Many of these have now gone, but not all. Three of the forts marked on the 1664 map were still in active use during WW1 (though they had been modernised over the years).

The Origins of the National Redoubt

Belgium won its independence from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830. With that Belgium inherited that kingdom’s existing fortifications within its borders (though they did have to drive the Dutch out of a few of them during the first few years of independence).

A few decades into independence, the rise of Napoleon the third worried the new country enough to bring the issue of national defence to the fore, and it’s out of this debate that the National Redoubt emerged.

It was not financially viable for a country as small as Belgium with so many land borders to adequately fortify all of them. Rather than doing a poor job of fortifying the entire country, it was instead decide to do a really good job fortifying one area. Should Belgium be invaded, the government could retreat into this so-called national redoubt, and hold out there until help could arrive from one of the guarantors of Belgian neutrality (primarily the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland). The location chosen to serve as the national redoubt was Antwerp. The city was the ideal choice for a number of reasons:

- It’s a major port city making it easy to supply and easy for help from abroad to arrive

- The city, and its access to the sea via the river Scheldt, were already well fortified

- The geography of the time made it easy to defend – the polders around the city could be flooded, obviating the need to build fortifications on many of the approaches to the city.

On the Eve of the National Redoubt

The National Redoubt, as a real project at least, came into being with an act of parliament in 1851. Before we can understand the changes heralded by this act, we need to have a look at the city’s defences just before the act was passed. The map below shows the defences of the city as they were in 1850.

The city’s defences in 1850 can be divided into three distinct categories – the city’s Spanish Walls, the forts along the river Scheldt, and a series of military inundation zones around the city.

De Spaanse Omwalling (The Spanish Walls)

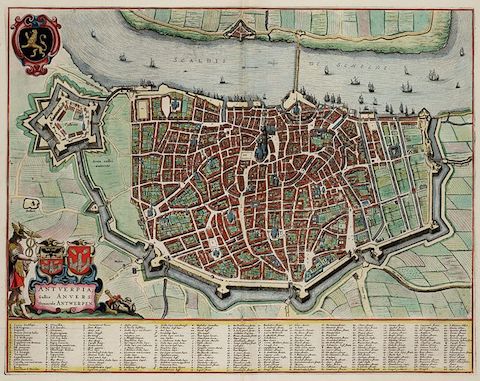

The building of the so-called Spaanse Omwalling, or Spanish Walls, was ordered by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1542, and the walls were completed in 1553. At this time Antwerp was the largest city in the Netherlands.

The walls were modernised and improved many times over the centuries. The most notable enhancement was the addition of a massive citadel at their southern end in the 16th century. This structure was known as de Citadel van Antwerp (the Citadel of Antwerp) or het Zuidkasteel (the South Castle), and built from 1567 to 1572.

Enhancements continued into the 19th century, with new fortifications (known as Lunets) being added as late as 1848.

The citadel was built with the dual purpose of defending the city from attack, and subduing any uprisings inside the city. The Citadel was used to bombard the city on a number of occasions over the centuries, leading to a resentment of military structures by many in the city which would last for generations. That legacy of mistrust would generate significant initial local resistance to the building of the national redoubt.

The outline of the walls on the map above shows how substantial these structures were – they were much more than just walls! The 1649 map below gives some idea of how impressive they were, even before many of the later improvements:

De Scheldeforten (The Scheldt Forts)

Defence of the river Scheldt has been strategically important for centuries, so after the impressive city walls and citadel, the next most impressive defensive structures were the forts that lined the river. These dated to the last half of the 16th century and the first decade of the 17th.

Furthest out from the city were the twin forts of Lillo and Liefkenshoek, both built on the orders of William of Orange in 1578. Closer to the city were the twin forts of Sint-Filips and Sint-Marie, which both date to 1584. When these forts were first built a bridge-head was constructed on each bank, and a floating bridge was erected, blockading the river. This floating bridge only lasted a year, but the forts remained for many centuries.

Finally, there were three forts on the left bank opposite the city. The largest of these was Fort Vlaams Hooft, which was built in 1583 directly opposite the centre of the city. In 1584 the small Fort Burcht was added down-stream directly opposite the citadel, and in 1609 another small fort, Fort Isabelle was added up-stream opposite the northern end of the city walls.

While I haven’t been able to find an exact date for when the two small forts opposite the city (Burcht & Isabelle) were decommissioned, I’ve found references to the forts being present but derelict by 1850, so it seems likely that these two small forts were already relics in 1850.

The Military Inundations

The fact that much of the land around the city was polder land was militarily vey useful. When the city was threatened the sluices could be opened to flood these polders, providing a natural defence around much of the north east, north, west, and south west of the city.

As the outskirts of the city developed, these inundations became impractical. While you could get away with drowning farmers at will in the 1600s, that kind of thing wouldn’t fly in the 20th century!

A False Start – De Kellerforten (The Keller Forts)

When it was decided to use Antwerp as the national redoubt, the city had already expanded beyond the limits of the spanish walls. These suburbs were completely unprotected, so the first new fortifications developed for the national redoubt were a set of seven small (by later norms) forts forward of the walls. These forts were not in a ring, but placed to protect certain villages and important infrastructure.

These early forts were originally known as Kellerforten (Keller Forts), after their designer, a certain M. M. Keller, who, as it happens did not exist. M. M. Keller was a pseudonym Brialmont used, presumably to shield himself from the strong local opposition to the building of these fortifications. The forts later became known as Fortje 1 to Fortje 7 in Flemish (and Fortin 1 to Fortin 7 in French). The je suffix in Flemish being a diminutive, comparable to prepending a word with wee in Scottish English. These wee forts were initially built as earthen banks with palisades, but were reinforced with brickwork before their completion.

Fortje 1 was built in near Merksem to protect the Bredabaan (road to Breda in the Netherlands), Fortjes 2, 3 and 4 were built to protect the town/village of Borgerhout, and Fortjes 5, 6, and 7 to protect the town/village of Berchem.

Before these wee forts were even completed in 1858, it was realised that they were already obsolete. Artillery had developed to the point that defences needed to be much further forward of the area they were defending to prevent bombardment. The decision was made to build a new wall around the city, forward of the spanish walls, and to build a ring of eight modern forts forward of this new wall to prevent enemy artillery firing over the new wall (see next section).

Fortje 1 was too close to the city, and it was seen as preventing the expansion of Merksem, so it was completely demolished, so much so that there is some debate about exactly where it was!

Fortje 2 was exceptional, it was located about half way between where the new ring of forts would be built, and where the new wall would be built, so it was retained, and it remained in use into the first world war. After the war the fort was demolished, with the moat being filled in and paved over to create a new suburban street. The floor plan of the fort’s redoubt building has been preserved as the floor plan of the Muggenberg sports aren.

Fortje 3 was demolished, and I was not able to find any trace of it, or even any hint of where it might once have stood. It’s location on the map above is a pure guess.

Fortje 4 was another notable exception – it was the only one of the Keller forts to find itself inside the new wall. This piece of military property within the safety of the new wall was too good to waste, and half of the fort was converted into an arsenal, and half into a military hospital.

The remaining three Keller Forts were incorporated into the new wall.

One other lasting change was made during the early 1850s, the Fort Vlaamse Hooft (the one directly opposite the centre of the city) was completely re-built. This new fort would be the first to have a design that would become synonymous with Brialmont – the fortification buildings were all on a large star-shaped island surrounded by a wide moat. The image below gives you a good idea of what it looked like:

A Fresh Start – De Brialmontforten (Brialmont Forts) and De Brialmont Omwalling (The Brialmont Walls)

In 1859 a new bill was passed authorising the building of a new larger city wall forward of the old Spanish Walls, and a ring of eight new forts forward of that. This was when Brialmont really got into his stride, and his name is intimately associated with all these works. Officially the new city walls were simply De Grote Omwalling (the big walls), but they were better known as De Brialmont Omwalling (the Brialmont walls). Similarly, what would later become known as the inner ring of forts was better known as the Brialmont Ring.

The new wall did not initially replace the spanish walls, and it originally connected with the citadel rather than the river at it’s southern end. At the northern end of the wall a second citadel was built, originally known as Het Noordkasteel (the north castle), but later known as Fort Noordkasteel. This new wall enclosed the docks of Antwerp as they then existed.

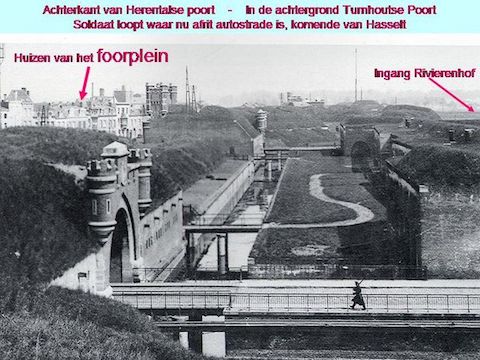

Although described as a wall, these walls were much more than that. They consisted of two parallel earthen banks with a moat between them reinforced with brick and stone, and containing monumental new city gates. The image below, and the website it is from (click the image to see the full page) give some idea of what the walls looked like:

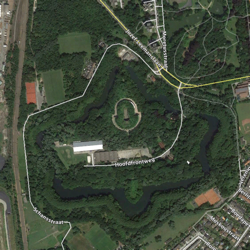

The ring of new forts formed an arc in front of the city stretching from the river Scheldt at Hoboken around to the inundation area at the river Schijn. These forts were the quintessential Brialmont-stle forts. They were built with of brick, accented with stone work, and designed to look impressive as well as beautiful. The fortifications were all housed on star-shaped islands with wide moats. Their shape is very easily recognisable from the air.

The photo of Fort 5 below will give you some idea of the architectural style:

A look at photos tagged with brialmontfort on Flickr will give a good oversight of what these forts looked like:

[flickr_tags user_id=”70519928@N00″ tags=”brialmontfort”]

The building of the new walls and forts altered the inundation zones somewhat, but they still formed an important part of the city’s defences.

The forts and the wall were completed by 1864.

Extending the Ring

With the completion of the new wall and its arc of eight protecting forts, it was time to finally get rid of the old spanish walls which were hampering the city’s growth. In 1870 the wall and the Zuidcasteel were decommissioned, and the long demolition process began. The line of the old wall would be used to lay four wide new boulevards, known as de Leien. These distinctive wide boulevards have fossilised the alignment of the old walls into the city’s street plan, and they are very obvious on both street maps and aerial/satellite imagery. The area once occupied by the large citadel was completely levelled, and developed into a whole new neighbourhood known as ‘t Zuid (the south). The Brialmont walls were re-aligned to connect to the river rather than the former citadel.

With the completion of the new wall and it’s arc of eight protecting Brialmont Forts, the easiest approach to the city (from the east along the wide strip of land between the river Scheldt and the canal to Liège) was well protected. Brialmont then turned his attention to fortifying the other approaches to the city. An 1870 act authorised the building of new forts to the north and west of the city, the renovation of some of the old forts along the river Scheldt, and the building of a new defensive dyke and accompanying changes to the inundations to the west of the city.

The vast majority of the work in this period focused on the left bank, to the west of the city, but there was one very important development in the north of the city, the building of a new fort in Merksem. Work on this Brialmont-style fort started in 1871, and was completed in 1882.

Up to this point there had been no defensive line forward of the left bank of the river Scheldt. The river itself was fortified, but the only thing forward of that fortification was an inundation zone. It was envisioned that the city of Antwerp would extend onto the left bank, so it was no longer viable to flood it each time the city was threatened – after all, who wanted to go live in a flood plain, or set up a business in one?

It was decided that the area now known as De Linkeroever (effectively the Borgerweert Polder) would become permanent dry land, and that new defences would be built to protect that area. These defences took the form of an arc of forts from the banks of the Scheldt near Schiphoek to the south of the city round to the Scheldt at the old Fort Sint-Marie. This fort, along with Fort Sint-Filips on the opposite bank would be re-built, and a third fort, Fort de Perel would be built close by forming a tight triangle of fortifications on that bend in the river. Finally a defensive dyke would be built between the new fort in Zwijndrecht and Fort Sint-Marie. This dyke would contain a redoubt about half way along its length, and act as a barrier to the inundation zone to its northwest.

With the building of the Fort van Kruibeke the southern inundation zone became unnecessary, so that was another piece of dry land that could be developed.

De Sperforten (The Bridgehead Forts)

The 1870 bombardment of Paris had shown that artillery had advanced to have a range of at least 7km, and the Belgians became worried that the ring of forts around Antwerp was too close to the city. The extra defences built in the 1870s helped somewhat, but more was needed.

From as early as 1872 the idea of using the rivers Rupel & Nete as a defensive line had been mooted. Together with the canal to Liège and the river Scheldt these two rivers form a large natural barrier around the eastern approach to the city, approximately along the line of the towns of Boom, Rumst, Duffel, Lier, Massenhoven, Olegem & Wijnegem. To support the use of this natural line of defence, four so-called Sperforten (bridgehead forts) were built, starting in 1878.

Work started with the two forts at the corners of the so-called Rupel-Nete line – the Fort van Walem to the south-east of the city, and the Fort van Lier to the east. These forts were both completed by 1883.

To the south of the city work started on what was then called Fort Rupelmonde, but later re-named to the Fort van Steendorp in 1882. It would take a decade to finish this fort.

The fourth and final bridgehead fort lay to the north east of the city in Schoten, and work did not start there until 1885, by which time the idea of bridgehead forts had already been replace with the concept of a large outer ring of forts, which this fort would become a part of (more in this in the next section).

While the bridgehead forts were being built, there were big changes in the city of Antwerp itself. The port urgently needed to expand beyond the Brialmont wall, so in 1881 the north section of the wall was removed, Fort Noordkasteel was reduced in size, and the port expanded out into what had been polder land. This affected the inundations to the north of the city, removing the Schijn inundation zone completely, and truncating the size of the northern inundation. It must have been obvious by this time that the northern inundation would soon have to go completely as the harbour continued to expand. Perhaps this is why two redoubts were built north of the city between 1878 and 1888.

The Summit – The Outer Ring

The national redoubt’s high point came in the lead up to the first world war. In 1883, before the bridgehead forts were even completed, it was decided to build a massive new outer ring of fortifications around the city that would incorporate the four bridgehead forts. This ring would consist of a combination of first and second order forts, redoubts, and sconces (in descending order of scale and firepower). In addition to this outer ring of fortifications, there would also be some redoubts built between the inner and outer rings to protect key infrastructure, notably the redoubt in Duffel to protect the railway line between Brussels and Antwerp, and the one in Kapellen to protect the railway line between Antwerp and Amsterdam.

It would take the better part of three decades finish this work, but on the eve of the outbreak of the first world war the outer ring was pretty much ready. All the structural work was completed, though some of the forts had not been fully armed yet.

While the majority of the ring consisted of traditional fortifications, there was one new inundation zone created between the Fort van Walem and the Fort van Breendonk. It had originally been planned to build a fort on this part of the line, but it was cut to save money. The low-lying sparsely populated area was ideal for inundating because it was surrounded by rivers and canals on three sides, and had another canal running through it.

The addition of the outer ring also had an impact closer to the city. The Brialmont walls were now obsolete, so they lost their military role in 1906. It took many decades to completely demolish them, but large gaps were cut into them to allow traffic to flow more freely into and out of the city. Like the Spanish Walls before them, the line of the Brialmont Walls has also been fossilised into the city’s street-scape. Their alignment was used to built the R1 motorway, better known as the Ring of Antwerp.

In the harbour region the two old river forts at Lillo and Liefkenshoek (which had not been modernised like Forts Sint-Marie and Sint-Filips) were decommissioned in 1894. In 1910 Fort Noordkasteel and the northern inundation zone were also decommissioned.

The First World War

The only real test of the national redoubt came during the first world war.

For Belgium, the war started when the Germans invaded the country on the 4th of August. The Germans did not invade Belgium because they wanted to capture Belgium, they simply needed to pass through it to reach their real target, France.

The day after the Germans invaded they started to lay siege to the fortified town of Liège (see these two posts for more), an important transport hub in the east of the country with good links down to France. Liège fell on the 16th of August, and the Germans then pursued two targets, they headed south to lay siege to the fortified city of Namur (see these two related posts) to open up a gateway into France, and they also pushed west and drove the Belgians into their national redoubt.

Once the Belgians had withdrawn behind the redoubt’s defences the Germans focused their efforts on France, attempting to break through quickly and take Paris before the French (with help from the British) could mount a strong defence. This plan failed, in part because the Belgians made three sorties out of their redoubt during September, forcing the Germans to divert resources away from France. By the end of September the Germans had had enough of this, and the decided to try take the redoubt and force a Belgian surrender. The siege on the national redoubt started on the 28th of September, and lasted until the 10th of October, when the city finally surrendered. This was not the end of the Belgian army though – they had managed to retreat from the city before it fell, first across the river to the left bank, and from there along the Dutch border and the coast down to the small corner of Belgium between the coast, the river Ijser, and the French border.

The Belgians never lost this final part of Belgium, and from there they fought with the French, British, and later Americans, to eventually win the war. The line of the Ijser river is where the dynamic war ended, and the hell of the trenches began. It’s along this line that you find the places we all remember from school like Ipres and Passendale.

The Belgians had believed their national redoubt impenetrable, and, while it did provide enough resistance to slow the Germans down, it did eventually fall. Why?

Simply put, by 1914 the redoubt was behind the times. Artillery had advanced faster than the Belgians could build and modify their fortifications. The forts that made up the national redoubt used regular concrete rather than reinforced concrete, and this was their Achilles heel – concrete could stand up to the Belgian’s own artillery, but it was no match for the brand new German ultra-heavy artillery. The so-called Big Berthas in particular made minced meat out of the forts.

It should be noted that while the national redoubt did fall, it can be argued that it did not fail. The redoubt succeeded in tying up the Germans just long enough to stop them reaching Paris before a defence could be mounted, and to stop the Germans from taking the entire country before help could arrive. While you can argue the redoubt was not a complete failure, it most certainly wasn’t a resounding success.

Between the Wars

Much of the retreat from the redoubt during the siege of Antwerp had been organised, so the retreating troops often had time to either put the weapons within the fortifications beyond use, or, in the case of smaller structures like sconces, blow them up completely, before leaving. Between the battle damage and the sabotage by the retreating troops, much of the redoubt was in a poor state after the Belgian withdrawal.

The occupying Germans made some repairs to the redoubt, and even some minor enhancements. This is particularly true of the section of the outer ring starting at the river Scheldt north west of the city and continuing to the north of the city, because the Belgian fortifications were incorporated into a defensive line the Germans constructed between Antwerp and Turnhout to protect occupied Belgium from an attack through the neutral Netherlands.

After the war the Belgians also made repairs to some of the forts, and added some enhancements like gas-proof chambers. However, there was no major investment in fortifying the country until 1934, when the threat posed by the rise of Nazi Germany focused minds on defence once more.

A Postscript – The PFA & KW Line

By 1934 the concept of the national redoubt was dead. It is was clear that days of concentrating military firepower inside defensive structures like forts was over. While many of the forts that once made up the outer ring of the national redoubt would be incorporated into new defensive lines, those forts would be used as infantry support posts rather than as heavy artillery positions.

There was also a much stronger focus on border defences and long defensive lines stretching over large parts of the country than there had been during the era of the national redoubt. You can get a good overview of Belgian defences as a whole during this era from the map and article linked below:

Click for Original Image & Article

Parts of the national redoubt were absorbed into the Position Fortifiée d’Anvers, or PFA, and the KW Line (named for the initials of the towns at each end of the position, Koningshooikt and Wavre).

To the north of the city the arc of forts and sconces from the Scheldt to the Albert Canal would be incorporated into a line of bunkers, and an anti-tank ditch would be dug forward of these bunkers. This would form part of the PFA. The section of the outer ring between Lier and Sint-Katelijne-Waver would be incorporated into another line of bunkers forming the start of the KW line. The forts in the outer ring between Walem and the river Scheldt would be used for command and control.

The rest of the outer ring, from the Scheldt north would cease to have any defensive role, as would the entire inner ring of forts. Many of these forts would remain in military ownership for decades to come, but they were no longer used as defensive structures. Instead, these former forts were as barracks, arsenals, storage depots, and even military gas factories.

For a deeper understanding of the PFA and the KW Line, I can highly recommend the article Deep Defences, Belgian Fortifications, May 1940.

When Belgium’s new defences were put to the test by the Nazi invasion on the 10th of May 1940, things didn’t go well. The design of the defences had assumed that the Ardenne forest was impenetrable by an army, and hence would act as a natural barrier. Yet again, military technology had evolved more quickly than the Belgians tactics, because modern German tanks of the day had no problems charging through forests like the Ardenne. Hitler did exactly what the Belgians had assumed was impossible, and sent his army through the Ardenne, and in doing so, out-flanked the Belgian defences. Belgium was overrun in just 18 days, surrendering on the 28th of May.

Final Thoughts

The very idea of a national redoubt seems bizarre within our modern united Europe, so it’s not surprising that Belgium’s national redoubt has all but vanished from the national consciousness. Many of the fortifications have disappeared from the landscape completely, and many of those that do remain are in a very poor state of repair. Quite a number have been converted to nature reserves, their many underground chambers and passages making ideal habitats for bats.

While many of the forts remain present in the landscape, the largest and most impressive structure within the national redoubt, the Brialmont walls, has as good as completely vanished. In the 1970s their alignment was used to built the R1 motorway. I think it reflects poorly on Antwerp that not a single monumental city gate, from either the Spanish or Brialmont walls, has survived. Two triangular shaped ponds in two small parks, and a few fortification-related street names is literally all that remains of the Brialmont walls.

Hopefully the remains of the national redoubt that have survived thus far will be preserved. It would be a real shame if 75 years worth of history were to be lost for ever. Lets hope that the recent re-opening of the Fort van Duffel as a tourist attraction is a sign of things to come.

[…] I was on three podcasts this week about the Apple announcements – check them out: the Daily Tech News Show with Scott Johnson and Veronica Belmont , the Mac Roundtable, and the SMR Podcast. I also did a guest Screencast for Don McAllister’s ScreenCasts Online all about Drop Shadow and AppDelete; watch the trailer at screenscastsonline.com. I describe how Apple gave me a fix (workaround) to my AppleTV problem, and I discuss our Sadomasochistic Relationship with Apple. Change the default behavior of a whole bunch of things in OSX using the GUI interface in donation ware Deeper from titanium.free.fr, makers of the awesome utility OnyX. In Chit Chat Across the Pond Bart breaks down the celebrity photo leaks and explains what actually happened and then after Security Lite he gives us a history lesson on World War I and how he used Google Earth to map out the progression over time of the defenses of Belgium, the National Redoubt. Read along and download the Google Earth file to play along as you listen at https://www.bartbusschots.ie/s/2014/09/14/antwerp-belgiums-national-redoubt […]

Wonderfully interesting. Thanks Bart for all the work. I have been listening to Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History series Blueprint for Armageddon in which he goes into great detail of how Belgium played such a large part in WWI. Your work makes much of this history come to life.

[…] described in detail in my recent post on Antwerp as Belgium’s national redoubt, in the late 1850s it was decided that the medieval walls of Antwerp needed to be replaced with new […]